How we interfaced single-threaded C++ with multi-threaded Rust and lived to tell the tale

This blog post is adapted from a talk Shuxian Wang and I gave at the Rust UnConf, organized by Rust NYC. The UnConf was a truly awesome group of Rust enthusiasts who met up for a couple hours for deep technical conversations and also gelato.

When you give us your software to test, we run it in containers on our deterministic hypervisor. The deterministic hypervisor (or Determinator) took us years to develop and replaces all non-deterministic operations (getting the time, anything involving random numbers, any inputs, etc.) with deterministic versions controlled by a stream of control signals. For a given set of control signals, the determinator will do exactly the same thing every single time.

The fuzzer

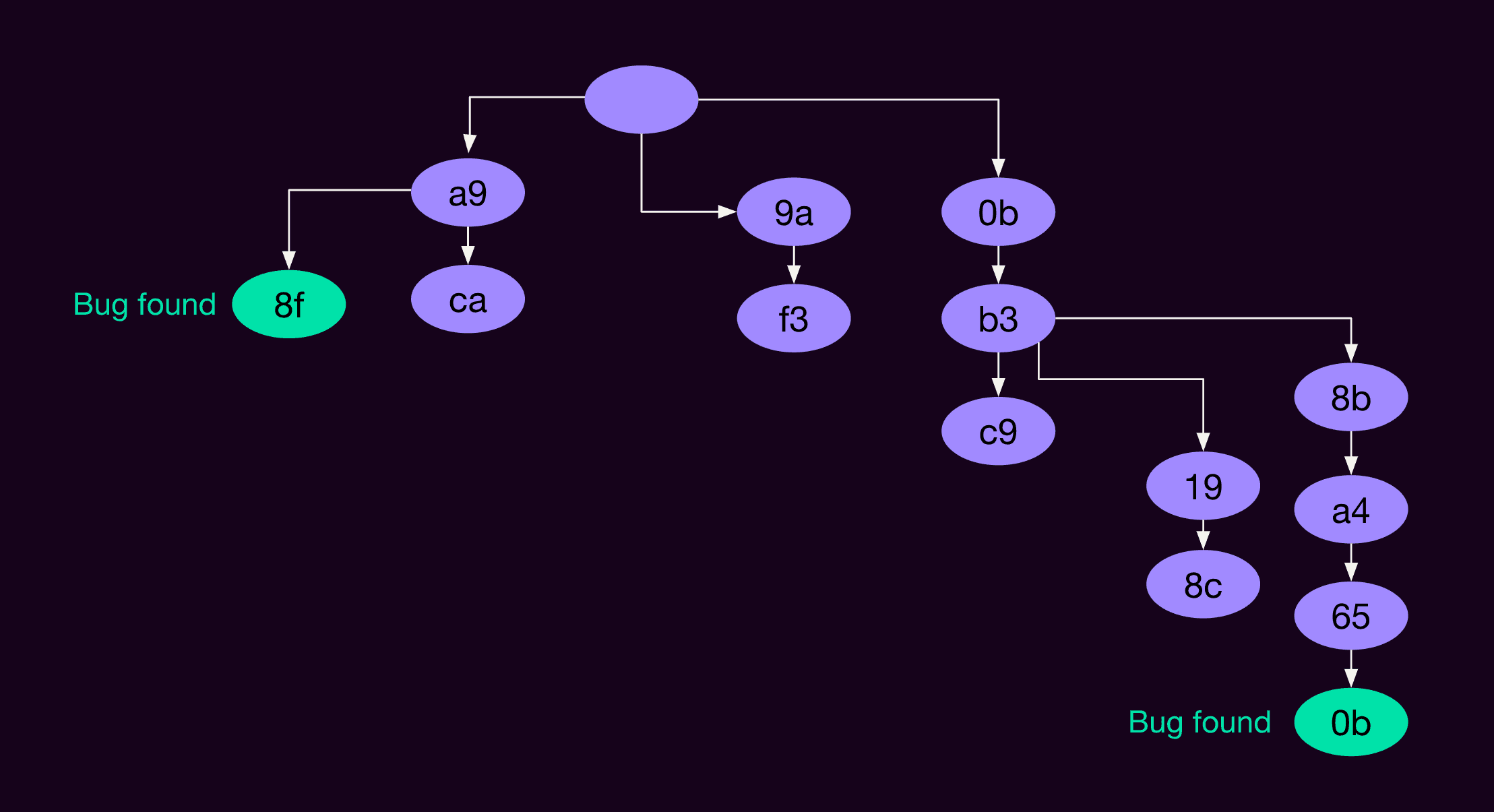

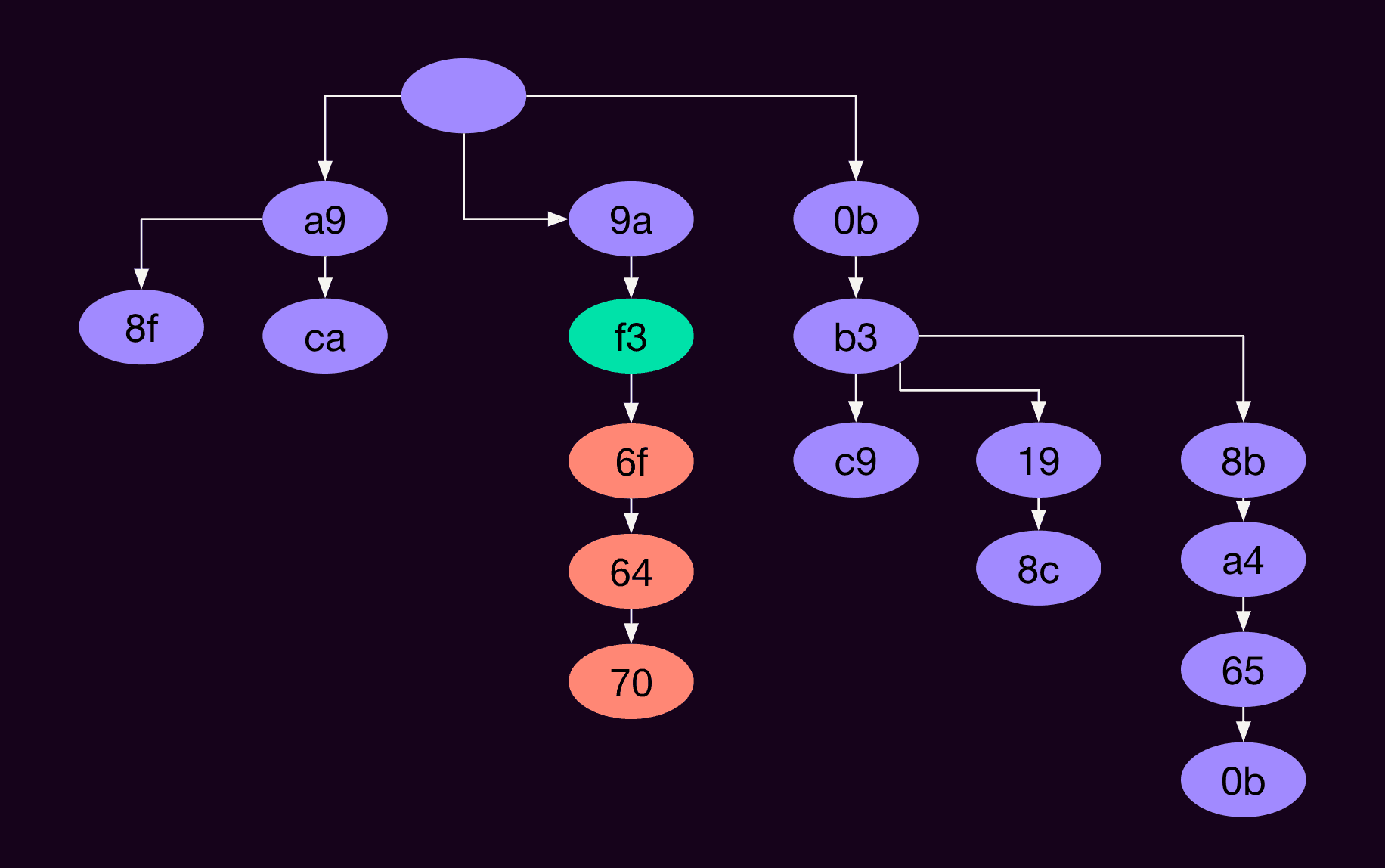

The Antithesis fuzzer is the program that controls all of this. It figures out which control signals to send to the Determinator to manipulate the system under test and find bugs. The fuzzer creates a state tree of control signal bytes, and some of those bytes find bugs and some don’t.

The controller

The logical part of the fuzzer, which I’ll call the controller, is responsible for figuring out where to start and what inputs to give. For example, in the image below, we’re starting at the green state (labeled f3) and providing input bytes 6f, 64, 70.

The fuzzer is written in single-threaded C++.1 We have different controllers that try to find bugs in different ways, and they all interact with the core fuzzer via a callback interface like this:2

poll_for_inputs(&controller) -> (start state, inputs)

advertise_outputs(&controller, states)The main loop of the fuzzer (1) calls into a controller’s poll_for_inputs method and asks “where should I start and what should I do?” and (2) calls into the controller’s advertise_outputs method and says “I did what you said, and here are the outputs3 that the system returned when run on the Determinator.”

A couple years ago we added the ability for the fuzzer to call into Rust, so that we could implement new control strategies more easily. We’ve been using that functionality to research new control strategies, but none of the Rust code is used in production. And the Rust side is multi-threaded and asynchronous. The Rust side’s controller uses an asynchronous interface of roughly “start here, give these inputs, and then await the outputs that come back,” rather than the callback-oriented C++ interface.

This post talks about how we interface multi-threaded asynchronous Rust with single-threaded synchronous C++. The story is 90% Rust and 10% C++, and it definitely goes into the weeds on the Rust side. But have no fear, we’ll come with you, and maybe even tell a joke or two as we go.

The basics

Let’s start with some background information. How do you combine C++ and Rust, without the added complexity of the asynchronous mismatch? And how do you combine any kind of synchronous and asynchronous code in Rust, without the added complexity of C++?

And what kind of problems come up when you combine the two?

Combining C++ and Rust

To interoperate Rust and C++, we use the Rust crate cxx, which creates a Foreign Function Interface (FFI) between C++ and Rust.4 It lets you define three kinds of things:

extern Rusttypes – Rust types that are exposed to C++. The cxx tooling creates a C++ header file that you include, and it generates code that converts C++ calling conventions to Rust calling conventions so that you can call from C++ into Rust.extern C++types – C++ types that are exposed to Rust. You specify the Rust signature for function calls, and cxx matches that up with existing C++ functions (according to some rules). Cxx converts the calling conventions appropriately so that your Rust code can call into C++ by simply calling a Rust function of the given signature.- shared structures – types that don’t have any methods/functions on them (i.e., just pure structs). You declare them in Rust and cxx creates a C++ header file so you can create them, use them, or both on the C++ side. You can pass these structs back and forth freely. The big difference between this and the previous two types is that these shared structures are only typed memory layouts; they don’t have executable function code on either side associated with them, so there’s no converting calling conventions.

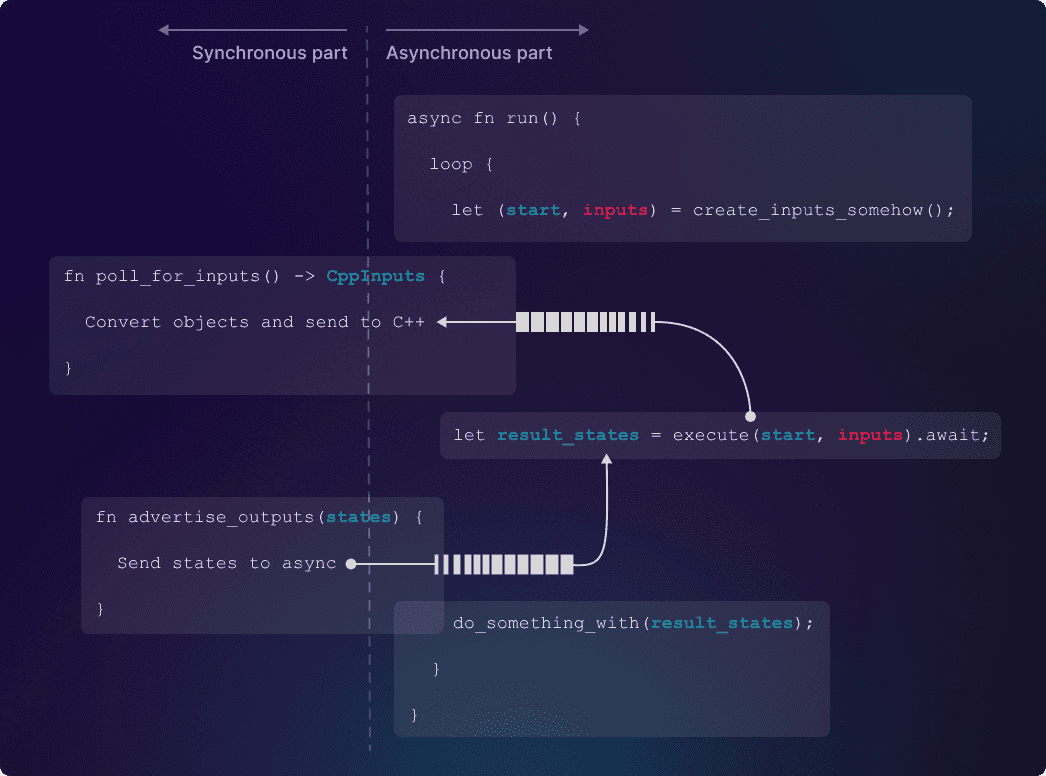

Combining sync and async

The core idea is that we’re going to write some asynchronous, multi-threaded Rust – the “asynchronous part” of the diagram below, and it will send information across async channels.5 The other end of those channels is in synchronous Rust, which is called synchronously from C++. The synchronous Rust will send and receive data from the async channels6 and convert back-and-forth between C++ format and Rust format. The more complicated controller logic will be pure Rust, isolated from having to worry about C++, either for object conversion or for sync/async mismatches.

Challenge 1: thread-unsafe objects

With the preliminaries out of the way, let’s dive a little deeper into the code pictured above.

There’s a technical challenge with this code: start and result_states are C++ objects (of type State), and we need to pass them back and forth across threads. When we call execute, we pass start from right to left, with run sending it and poll_for_inputs receiving it. And then in advertise_outputs, we pass result_states from left to right with run receiving it. By default, cxx doesn’t implement Send or Sync for C++ types. (We also send inputs, but that’s a Rust-native object.)

Interlude – Send and Sync

No talk of thread safety in Rust would be complete without a discussion of Send and Sync. Send and Sync are two marker traits (i.e., traits that have no methods) that tell you – and more importantly tell the compiler – what thread-related operations are and aren’t safe to do with a type.

Paraphrasing the standard library documentation slightly:

- A type

TisSendif it is safe to have exclusive access (Tor&mut T) across different threads - A type

TisSyncif it is safe to have shared access (&T) across different threads

There’s a well-known consequence that T is Sync if and only if &T is Send.

Usually the compiler implements Send and Sync for you automatically, based on reasoning about the Rust code. Of course, the Rust compiler can’t reason about C++ code, so it doesn’t implement them for you automatically, but you can implement them manually if it makes sense to do so.

Back to the problem

I suppose this would be a good time to mention that I’ve been programming in C++ since the 90s, and in Rust for about 2 years and a little bit. And that the events we’re talking about happened 2 years ago, when I was brand new to Rust. At least that’s my excuse.

The Rust compiler complained that it couldn’t pass State across thread boundaries because it didn’t implement Send, so I wrote this code:

unsafe impl Send for State {}Pop quiz: do you think this ended well?

Of course it didn’t. This causes an intermittent seg fault. Which as we all know, shouldn’t be possible in Rust code. Unless you do something unsafe that you really shouldn’t have.

Why, specifically, did this fail?

On the C++ side, there’s some code like this:

struct State {

ref_ptr<StateImpl> impl;

...

}Here ref_ptr is a class that implements a reference counted pointer. Similar to Rc or Arc in Rust or shared_ptr in C++. In particular, ref_ptr isn’t thread safe. So when we’re using State objects on the Rust side, sometimes we hit a race condition7 where we get the wrong value of the reference count and then delete an object that is still being used; when we go to access that object, we get the segfault.

So clearly State isn’t Send. We can only do things that affect the refcount (clone or drop) on the main C++ thread. Phrased as in the interlude: it’s not safe to own a State in another thread, because cloning it and dropping it (operations you can do if you own T) change the refcount, which isn’t safe to do in other threads. For the same reason, it’s not safe to have a &State in another thread, because you could clone the shared reference on the other thread.

The solution

Other than cloning and dropping - things that affect the refcount - we should be okay to use State on different threads, as long as we keep the underlying object around long enough. So we came up with this solution.

The solution involves two Rust structs. CppOwner only lives on the main thread and owns the original C++ object. CppBorrower acts like a reference to the C++ object. CppBorrower is fine to pass around between threads; CppOwner needs to live on the main thread. When you want to drop things, you have to drop all CppBorrowers first, then drop the CppOwner (on the main thread).

On the main thread only:

pub struct CppOwner<T> {

value: Arc<T>

}

impl<T> CppOwner<T> {

pub fn borrow(&self) -> CppBorrower<T> {

CppBorrower { value: self.value.clone() }

}

pub fn has_borrowers(&self) -> bool {

Arc::strong_count(&self.value) > 1

}

}

impl<T> Drop for CppOwner<T> {

fn drop(&mut self) {

if self.has_borrowers() {

panic!("No!");

}

}

}On all threads:

pub struct CppBorrower<T> {

value: Arc<T>

}

impl<T> Clone for CppBorrower<T> {

fn clone(&self) -> Self {

Self { value: self.value.clone() }

}

}

unsafe impl<T: Sync> Send for CppBorrower<T> {}

impl Deref ...To use this, we create a CppOwner on the main thread and keep it around in an “in flight” set, then pass a CppBorrower around where we need it:

// On the main thread

let cpp_state = CppOwner::new(state.cpp_clone());

channel.send(cpp_state.borrow()); // Send borrow to other threads via the async channel

self.in_flight.insert(cpp_state);Later, but also on the main thread, we check for “in flight” C++ objects that no longer have any borrowers, and drop them:

// Later, but still on the main thread

self.in_flight.retain(|s| s.has_borrowers());You can look at the mechanics in the code above; we’re using Arc to give us the refcount we need and make it possible to pass things around.

Summarizing this: we make CppOwners on the main thread and keep track of them in the “in flight” set. We make CppBorrowers on demand and pass them around freely. We garbage collect a CppOwner on the main thread when it has no more CppBorrowers. And because the only operations that affect the (C++) refcount happen in CppOwner, on the main thread, we avoid the race condition we had before.

The design challenge

This approach works. We used it for about two years.

And then something happened that made us question our design choices: someone else tried to use the Rust interface to the fuzzer. For production code!

This caused us to think harder about the methodology. The garbage collection isn’t very efficient – from time to time we loop through all the CppOwners that exist and say “should I delete you?” If we do that very frequently, we’ll do a lot of wasted work. If we do it very infrequently, we’ll use a lot more memory than we should. Fundamentally, the amount of work we should be doing should be proportional to number of deletions, but our current implementation is proportional to number of objects. Or maybe to number of objects X number of iterations. For the research work flows we had, this worked out okay, because we didn’t have a lot of objects around at the same time, but for the production case, it was problematic. (Said another way, the amount of work depends on the number of objects we keep around, rather than the smaller number we delete.)

A better solution

Previously, CppOwner had an Arc<T> (where T is a C++ type).

struct CppOwner<T> {

value: Arc<T>

}And CppOwner had to remain on the main thread and we could only pass CppBorrowers around.

Our new solution is to make CppOwner own T directly (not Arc<T>).

struct CppOwner<T> {

value: T

}and pass Arc<CppOwner<T>> around. To do that safely, when the last refcount goes away and we drop CppOwner<T>, we send T back to the main thread for deletion.

This sounds like a great plan, but it immediately hits a snag. We can only do that if CppOwner<T> is Send, which only happens automatically if T is Send. And we don’t want every C++ type to unsafe impl Send (we saw how dangerous that was before with the segfault). So how can CppOwner<T> be Send when T is not Send?

SendWrapper

There’s a saying in computer science that you can solve everything with one more layer of indirection. Let’s try that.

Here’s a struct SendWrapper<T> that can smuggle T across thread boundaries:

pub struct SendWrapper<T>(T);

// Even when T: !Send

unsafe impl<T> Send for SendWrapper<T> {}The key here is the comment: SendWrapper<T> is Send even if T itself isn’t.

But, since T may or may not be Send, it’s not safe to get exclusive access to T, so we have to be careful that SendWrapper<T> prevents that. It’s fairly easy not to expose any way to get &mut T (for example, SendWrapper doesn’t implement DerefMut), but we also have to make sure you don’t drop a SendWrapper. So we wrote code like this:

impl<T> Drop for SendWrapper<T> {

fn drop(&mut self) {

panic!("Cannot drop a SendWrapper!")

}

}A better CppOwner

Now we want to put the right logic in CppOwner to send T back to the main thread when we drop.

pub struct CppOwner<T>(ManuallyDrop<SendWrapper<T>>);CppOwner now contains a SendWrapper (wrapped in ManuallyDrop, “A wrapper to inhibit the compiler from automatically calling T’s destructor.”).

Our Drop implementation for CppOwner pulls the SendWrapper and pushes it into a special “drop queue” that sends it back to the main thread:

impl<T> Drop for CppOwner<T> {

fn drop(&mut self) {

let val: SendWrapper<T> = unsafe { ManuallyDrop::take(&mut self.0) };

DROP_QUEUE.push(val);

}

}Wait, what’s this DROP_QUEUE? It’s a static instance of a new DropQueue type. The type is defined as:

pub struct DropQueue<T>(ConcurrentQueue<SendWrapper<T>>);And DropQueue has a drain method that you call on the main thread to extract and drop T. (It’s only safe to call drain on the main thread, because it’s only safe to drop T on the main thread.)

impl<T> DropQueue<T> {

// SAFETY: Only call on main thread

pub unsafe fn drain(&self) {

for val in self.0.try_iter() {

drop(unsafe { val.unwrap_unchecked() })

}

}

}This uses another function on SendWrapper that we didn’t talk about – an unsafe method to get the T out of SendWrapper.8

impl<T> SendWrapper<T> {

pub unsafe fn unwrap_unchecked(self) -> T

}We’ve now solved the garbage collection problem. CppOwner’s drop method sends the object back to the main thread for destruction, and we only do work proportional to the number of things we need to drop, not to the number of iterations. Moreover, we’ve mostly gotten rid of CppBorrower, replacing it with Arc<CppOwner>.

Challenge 2: thread-unsafe functions

Let’s back up time to when we had the original solution of garbage collection, with CppOwner and CppBorrower, but before the SendWrapper improvement. At that time, we found another problem.

Here’s some code we had written:

async fn run() {

loop {

let (start, inputs) = create_rollout_somehow();

let result_states = execute(start, inputs).await;

let details = result_states.get_details();

do_something_with(details);

}

}In this code, start is a C++ object of type State, which we had converted to a CppOwner<State> and CppBorrower<State>, so garbage collection/refcounting worked correctly. But get_details,9 a function on the C++ side, isn’t safe to call across threads; it can only be called safely on the main thread. (More generally, functions on the C++ side may or may not be safe to call across threads; this particular one isn’t.)

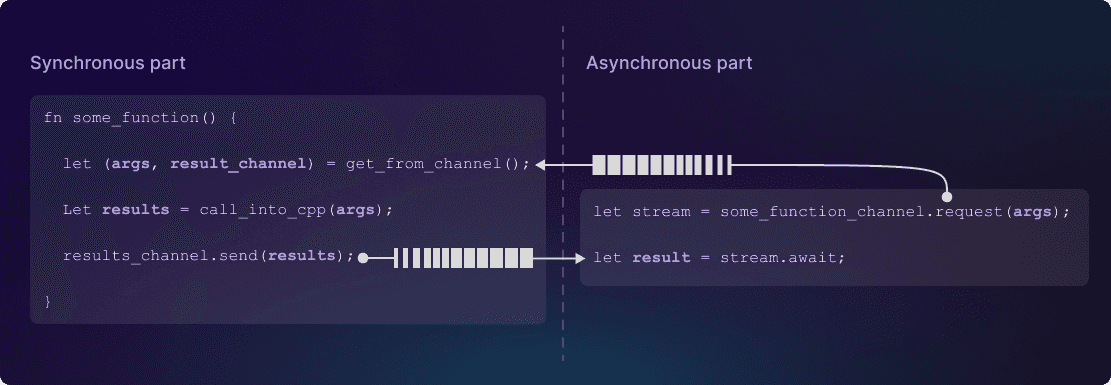

First solution

There’s a solution to this too:

Whenever we have a function (like get_details) that can only be called on the main thread, rather than call that function, we go through a layer of indirection.

In the asynchronous part, we:

- create a request object with the parameters to the function

- pass the request object across the thread boundary via a “request” channel

In the synchronous Rust part we:

- poll the channel for the request object

- call the C++ function with the given parameters

- push the results into a second, async “results” channel

On the async side, we then await the results of this “results” channel.

This general pattern worked; we just had to be careful about what we called on the main thread and what we called on arbitrary threads.

The design challenge

As we started preparing this for production, one concern was the very subtle thread-safety story. Rust has the model that a struct is either thread-safe or it isn’t (and there are two kinds of thread-safety: Send and Sync). But what we found is that some methods on a struct may be thread safe but others aren’t. This mismatch between the languages is fairly fundamental; it’s not that either one is right or wrong, they’re just different. And we need to make them work together.

Also, the initial solution feels right to me as a C++ programmer, but not to me as a Rust programmer. It boils down to “be very careful and think really hard about what you’re doing” – that’s totally the vibe of writing this kind of code in C++. But in Rust, that isn’t the vibe. The Rust way is “enlist the compiler’s help to find problems for you, rather than you have to find them manually.” My initial solution wasn’t very Rust-y at all.

Summarizing this problem, we want to:

- deal with “functions you can only call on the main thread”

- figure out how to model the partial thread safety of some of our C++ types

- be safe and ergonomic, so other people on the team can use it without introducing subtle bugs

- define well-documented safety obligations for the C++ code (what kinds of things are you and aren’t you allowed to do in C++ code that’ll interact with Rust code?)

A better solution

The better, more Rust-y solution involves two pieces: (1) The MainThreadToken, which we can use to ensure that a certain function can only be called on the main thread, and (2) a set of conventions and rules for which functions are and aren’t safe to call on other threads.

The MainThreadToken

We want to mark functions as only callable on the main thread, so we invented a MainThreadToken struct. It is a proof-carrier: having a MainThreadToken means you’re on the main thread. The code is deceptively simple:

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

pub struct MainThreadToken(PhantomData<*mut ()>);If you haven’t ever used PhantomData, it’s a Rust construct that doesn’t actually store any data; it just tells the compiler “pretend this thing has this type.” So this whole token takes 0 bytes of RAM, but acts like it has a type of *mut(). The *mut ensures that the struct isn’t Send or Sync.

I’ve pulled a bit of a fast one on you. This code ensures that you can’t pass a MainThreadToken between threads, but there’s no guarantee that you made it on the main thread, you could have made it on any other thread and it’d be stuck on that thread, not the main C++ thread. So there’s a little more code:

pub static MAIN_THREAD_ID . . .

// Somewhere guaranteed to be in the main thread

initialize(MAIN_THREAD_ID);

/// # Safety

/// This function must be called from the main fuzzer thread.

pub unsafe fn new() -> Self {

assert_eq!(*MAIN_THREAD_ID, std::thread::current().id());

Self(PhantomData)

}There are two overlapping controls here. (1) The unsafe keyword and the safety comment should be enough to ensure you use this correctly. But then we also have (2) a runtime check, so if you don’t use it correctly, you’ll get a panic rather than undefined behavior.10

In general, you shouldn’t be calling this new() much. You can call it once, and then Copy or Clone the resulting token (on the same thread).

How does this help us? If we have a function that’s only safe to call on the main thread, like, for example, the drain method we talked about before:

// SAFETY: Only call on main thread

pub unsafe fn drain(&self)We can make it safe with the MainThreadToken:

pub fn drain(&self, _token: MainThreadToken)We don’t actually use the MainThreadToken anywhere in the implementation; just the fact that you have it and are able to call the function with it means that we’re on the main thread. So the compiler can statically check that you’re only calling a method (like drain) where you should be.

Modeling thread safety for our C++ types

The cxx crate distinguishes between two types of C++ methods: const methods (which become &self on the Rust side) and non-const methods (which become Pin<&mut Self> on the Rust side).

| C++ | Rust |

|---|---|

int get_data() const; |

fn get_data(&self) -> i32; |

void push(int x); |

fn push(self: Pin<&mut Self>, x: i32) -> (); |

We’re going to leave the non-const ones as they are – the &mut Self ensures that you never call these concurrently, and SendWrapper specifically avoids giving you &mut access – so the non-const functions are only callable on the main thread from C++.

The const methods are a bit of a trick though. const in C++ means that the binary bits of the representation don’t change in the function. But it’s totally possible that a class has a pointer to another class, and even though the pointer isn’t changing, something in the other class is changing concurrently.11

For example, if some other code has a copy of the other pointer, it could change x and affect the value returned by do_const.

struct Other {

int x;

};

struct MyObj {

Other* other;

int do_const() const {

return other->x;

}

};Going a step further, do_const can’t change the pointer other, but it can change other->x. So other->x++ is completely valid in do_const.

Sync and Unsync methods

Evidently const is not enough to tell us whether a C++ method is or is not safe to call on other threads, so we’ll make our own distinction. We’ll call things that are safe to call on other threads “sync” and things that aren’t “unsync.” (Exact definitions below.)

On the C++ side, we define two dumb “marker macros” for SYNC and UNSYNC:

#define SYNC

#define UNSYNCThese don’t actually do anything. But we can use them to label our functions. For example:

int get_immutable_data() SYNC const;

int get_mutable_data() UNSYNC const;For example, you could imagine get_immutable_data returns the value of an ID that’s set in the constructor, and get_mutable_data dereferences a pointer and returns some value from that, where the internals of the underlying object may change (like in the MyObj example above).

These macros aren’t for the compiler; they’re for us. When we’re defining a class, it’s really easy to see during code review (1) did someone use SYNC and UNSYNC? and (2) did they do it correctly? If they didn’t use the macros at all, we send the code review back with “please figure this out and add it.” There’s also a really long comment where the macros are defined saying exactly what the obligations are (imagine this blog post in the form of a comment).

While we’re at it, let’s change the name of the unsync function to emphasize that it’s unsync. That doesn’t help us right now, but it will help us when we get to Rust.12

So now we have:

int get_immutable_data() SYNC const;

int get_mutable_data_unsync() UNSYNC const;What are Sync and Unsync methods?

So what exactly does this made-up SYNC/UNSYNC distinction mean:

- Non-const methods can have exclusive access. For example: non-atomic writes, constructor/destructor

- const, sync methods can have synchronized shared access. These functions are thread-safe without external synchronization. For example: reading immutable data, atomic operations, operations where the C++ class implements synchronization

- const, unsync methods can have unsynchronized shared access. These functions are only safe to call with external synchronization. For example: non-atomic read on mutable data

It must be the case that “const, sync” are safe to call concurrently with other “const, sync” methods and with “const, unsync” methods. But “const, unsync” methods are only safe to call with “const, sync” methods, not with other “const, unsync” methods. And neither is safe to call concurrently with non-const methods, which we’ll summarize in this table:

| Concurrency safe? | non-const | const, sync | const, unsync |

|---|---|---|---|

| non-const | N | N | N |

| const, sync | N | Y | Y |

| const, unsync | N | Y | N |

Sync and Unsync methods on the Rust side

For SYNC methods like this:

int get_immutable_data() SYNC const;on the Rust side, we just use the default signatures, like:

fn get_immutable_data(&self) -> i32;For UNSYNC methods like this:

int get_mutable_data_unsync() UNSYNC const;on the Rust side, we make the method unsafe and add a Safety comment:

/// # Safety: main thread only

unsafe fn get_mutable_data_unsync(&self) -> i32;At this point, we can mark the Rust type (which cxx derived from the C++ type) as Sync. Not Send, just Sync (meaning it’s safe to have a shared reference to it).

Finally, we use MainThreadToken to make a safe version of the _unsync function:13

fn get_mutable_data(&self, _token: MainThreadToken) -> i32 {

// SAFETY: We're on the main fuzzer thread as we own a `MainThreadToken`.

unsafe { self.get_mutable_data_unsync() }

}Anyone using this class should call the safe version of the function. (This is also why we added the _unsync to the end of the function name, so that the safe version could have the non-weird name.)

Calling C++ methods in other threads

Let’s look back at SendWrapper<T> for a second. We didn’t say this before, but here are some implementations:

unsafe impl<T> Send for SendWrapper<T> {}

// &SendWrapper<T> -> &T, only if T is Sync

impl<T: Sync> Deref for SendWrapper<T> . . .So SendWrapper always implements Send, regardless of whether or not T does, but it only implements Deref if T implements Sync. So you: (1) can’t get a T or a &mut T, (2) can only get a &T if T is Sync (i.e., if &T is safe to use across thread boundaries).

Wow, that’s kind of a mouthful. What does it mean? It means we can define a couple different kinds of Rust structs derived from C++ structs:

- Structs that can be smuggled around in

SendWrapper<T>, but that you can’t call any methods on in other threads - Structs whose methods you can call in other threads

If you stare at that for a while, you might wonder why type (1) would ever be useful. The key is the last couple words: “you can’t call any methods on in other threads.” Using the request object model, we can pass SendWrapper<T> back and forth across threads, and then call the methods in the main thread.

For case (2), our implementation of Deref means that we need to implement Sync on the original C++ type T to be able to call functions on a class on different threads:

// Long #Safety comment

unsafe impl Sync for SomeCppType {}As before, we have a long Safety comment explaining this whole scheme and your obligations in the part of the cxx file14 where the impl Sync lines go.

Summarizing the method, if we want to call any functions on a type on different threads, we do the following:

On the C++ side, we:

- use

SYNCorUNSYNCmarkers on each const method depending on whether or not it’s safe to call the method on multiple threads.15 - name unsync functions using a suffix

_unsync. - use code review to confirm all the correct obligations are upheld.

On the Rust side, we:

- use the same name as the C++ side

- make any

_unsyncmethodsunsafewith an appropriate Safety comment. (The Safety comment is by convention, but clippy helps us to enforce it.)

- make a safe version of the

_unsyncfunction, without the_unsyncsuffix, by using theMainThreadToken.16 - mark the type as

Sync. (The unsafe_unsyncmethods “opt-out” of that, and the safe versions of those_unsyncmethods require theMainThreadToken, which enforces the right thread.)

This solution is much more “Rust-y,” but also makes the C++ programmer in me happy. On the C++ side, we’ve defined some things exactly and know what to check in code review. That ensures that the functions we expose are properly constructed. (The C++ programmer in me is okay with having “and be careful and a developer will verify something during code review” as long as I have a clear definition of what that something is.) On the Rust side, once we’ve applied the rules above, the compiler can check that where the functions are used, they’re used correctly. And the combination of the two ensures that the whole thing works together.

Summarizing the methodology

I’ve covered a lot of material here. We’re using cxx to call from C++ into Rust, and the C++ code is single-threaded, but the Rust code is multi-threaded. This causes several problems.

The first problem is non-thread-safe objects, which we originally solved using CppOwner and CppBorrower structs. Then we improved the solution with a new version of CppOwner that included a SendWrapper struct to smuggle a C++ type across thread boundaries, and CppOwner handled dropping by sending the SendWrapper back to the main thread, where it can safely be deleted.

The second problem is non-thread-safe functions. We solved that by creating some conventions for naming and tagging functions on the C++ side, and then marking some functions on the Rust side as unsafe. We also created a proof-carrier type called MainThreadToken, which you can only have on the main thread. Using that, we made safe versions of the unsafe functions.

By the time we got to the second/later solution of both problems, we had converted to a very Rust-y solution, where the compiler has the information it needs to ensure you are calling things correctly. So the Rust part of the fuzzer is ready to use in production, even by other developers.

Making it even better: formalism

If you’ve made it this far and are thinking “what I don’t like about this post is that it’s too short and doesn’t go into the weeds enough,” I have good news for you. There’s a Part 2 on the way, where my co-conspirator Shuxian explains how we formally proved that these primitives have the behavior we’ve claimed.